As the 3rd anniversary of that horrible day approaches, there has been a lot of talk about the 16th. I talked about the experience for the third time the other night. Having talked about it, I decided to take some time to write about my experience. This is over simplified and long, but it will be well documented as my journey over the past 3 years over the next 2 weeks leading up to the anniversary.

Part 4: The Midnight Disease

Lying in the hard bed of my hotel room, clutching my chest, I struggled to breathe. My roommate for the weekend, a Harvard undergrad, was still downstairs, conversing with the other visitors to the Miami University campus. The dinner, which I had left, was very divided, as the Xavier University students, and their fellow Ohio hosts, isolated themselves amongst three tables farthest from the food. My dank joylessness of the event was only emphasized by the remainder of us sitting among the faculty, discussing the topics of our papers to be discussed throughout the course of the conference. Settled there, trying to eat cold baked ziti, I felt that I had surpassed my manageable doldrums for that day. I began to sense the onset of the symptoms at mid-afternoon or a little later – gloom crowding in on me, a sense of dread and alienation and, above all, stifling anxiety. The pain persisted during the opening remarks and reached an apex in the next hour when, back in my room, I fell onto the bed and lay fixated on the ceiling, immobilized and in a trance of supreme discomfort. Rational thought was usually absent from my mind at such times. I can think of no more apposite word for this state of being, a condition of helpless stupor in which cognition was replaced by positive and active anguish. I clearly recall thinking, as I lay there, that my afternoons and evenings were becoming almost measurably worse, and that this episode was the worst to date. Nevertheless, I somehow managed to reassemble myself for the keynote address, by a Columbia University professor who thought the conference so belittling, he had not completed his research and paper presentation.

Earlier in the week, I had dealt with my sleeplessness by watching some of the longest movies ever made. I sought comfort in-between my daily activities, of lying in my dorm room, watching Numb, while my roommate slept above me. During my morning hours I read, to the point of memorization, the daily spring training updates, while I enjoyed the racy comments of Howard Stern on my XM radio. Unbeknownst to me at the time, the show would motivate me for the first time in months to do something during the course of the day. A guest on the show, making light of comedian Artie Lange’s depression, mentioned in passing a book by William Styron.

William Styron’s Darkness Visible, his memoir of dealing with depression, became my reading for the rest of my weekend in Ohio. I had picked it up at a Barnes & Noble in West Virginia along my route, and, sitting alone in the brisk hotel lobby, I consumed a six-pack of Rolling Rock, finishing the book that first night. For the first time I could express to someone the emotions that I felt, or lack thereof, and sought a way to connect with those in my life once again.

Styron’s memoir was a reaction piece, first published in the New York Times. Recounting the circumstances that led to Darkness Visible: A Memoir of Madness, William Styron claims he decided to write his memoir as a horrified response to Primo Levi’s suicide in 1987, only his horror was not at the suicide itself but rather the published reaction to it. In "annoyance" with such ignorance, Styron argued, "the pain of severe depression is quite un-imaginable to those who have not suffered it" and "to the tragic legion who are compelled to destroy themselves there should be no more reproof attached than to the victims of terminal cancer."

While reading the book I was overcome with the same sense of disgust towards the media reaction of Primo Levi that William Styron felt, both because of my own sense of the disease as well as Styron’s keen sense of writing. William Styron’s memoir works to follow the beginning of his disease until his ultimate recovery. Following the multiple stages of psychoanalysis and psychopharmacology, as parallel to his lack of improvement after treatment, with the ultimate expression that the disease he suffers from is such a thing, and not a weakness of one’s body, soul, and will, as those observed following the death of Primo Levi. It is therefore my will to further enhance his sentiment, by comparing various stages of his treatment to my own, and how there is still a resentment in today’s media against those with depression, regardless of the modern science proving its worthiness as a disease, or those who, among celebrity status, have the disease themselves.

In Styron’s Darkness Visible, he expresses his opinion that depression is a genetic trait, which can be traced back through one’s family lines. He emphasizes that this trait needs a trigger, or catalyst, to become apparent to the victim, and that once the catalyst appears, the disease will manifest, regardless of the victim’s awareness of the progression of the disease. While not going into his family history, he does state that his catalyst is his alcohol withdrawal. He quit drinking, not because he wanted to, but because one day he could no longer stomach the taste of alcohol, and his body forced him to quit. While the idea of a depressant acting to suppress his depression for so many years prior may seem contrary to scientific probabilities, after his recovery from the disease he, rereading his own books, saw his depressive symptoms manifest themselves in the pages of his works and characters, and the evolution of his disease prior. The alcohol served to give him a euphoric sense of being, surpassing the pain, which is one that an alcoholic would search to escape and find in drinking. Meanwhile, it is also proven that the frontal lobes, which are the source of creativity, are also the source of depressive feelings, as well as the effects of alcohol. The alcohol, therefore, could be seen as having aided him in his writings, as it is said to have so many writers, painters, and artists before him.

Only two weeks prior to my trip to Miami University, my freshman year roommate had been prevented from attempting suicide by a passerby, and reawakened an understanding between us that had existed for three years. During our freshman year as cadets, mindless souls that we were, scurrying through the halls of Brodie, seeking to escape sight of the upperclassmen, we would meet friends of ours that lived on the civilian side of campus, of which we would introduce each other. He was a man of medium stature, overweight, but typical of a high school football lineman, and of Caucasian and Asian descent. Commonly reading manga in our room, he had been always been a quiet person, and, although he had participated in high school sports, still new the feeling of being alone and in the shadows. When he introduced me to his fellow Asian friend, I made no notice to the blank stare and expressions of depression that my roommate and I would later share, nor did his face stand out simply by its makeup. Regardless, his plain face would be one to haunt us both, possibly, for the rest of our lives.

In my case, my mother’s side of the family is known to have depression. My grandmother developed alcoholism early in her marriage, both because of my grandfather’s personality as well as her first child having been born retarded. While she still had two more children, the disorder was already there, and the alcoholism of my grandmother, as well as their divorce, served as the catalyst for my mother’s depression. While my grandmother has recovered, and now takes antidepressants, along with my mother and uncle, it was only my depression that was not produced by family issues. My symptoms were hidden until an acquaintance whom I had previously met a year prior changed my world, as well as that of this campus.

Styron’s visit to Paris served as his self awareness that he needed to seek psychiatric help. this passage was the main part of the paper that the New York Times printed as his rebuttal to the press reaction to Primo Levi’s death. Serving as the opening chapter, it describes a trip of his to Paris to receive an award for a short story that had been translated into French, and his realization that his feelings of anxiety were taking over his daily life. His daily routine had been significantly altered by the disease, which prevented his ability to write, as well as to function properly within society and his marriage. He no longer slept, not just in his daily afternoon naps that his career had afforded him, but also at night, where he lay restless in bed, exhausted but until to find peace at night. During his trip, he comes to realize that this may possibly be the last time he sees France, a country he had come to love, and in so documenting it, helped me to see how far that I had come in my own right.

I no longer attended class, for fear of the horrors that I would daydream of while sitting there. The gunshots wrung through my head as I sat, twitching nervously, waiting for the class to end. I was beyond focusing on the work at hand, but, rather, bought a Live Scribe pen so that afterwards I may be able to go over the notes that I was unable to take while in the classroom. Only days before I had concluded that I was suffering from a serious depressive illness, and was floundering helplessly in my efforts to deal with it. I wasn’t excited by the privileged occasion that had brought me to Ohio. Of the many dreadful manifestations of the disease, both physical and psychological, a sense of self-hatred – or, put less categorically, a failure of self-esteem – is one of the most universally experienced symptoms, and I had suffered more and more from general feeling of worthlessness as the malady had progressed. My dank joylessness was therefore all the more ironic because I had driven to Ohio on grant money from Virginia Tech, after they had funded my undergraduate research on Marcus Atilius Regulus. Had I been able to foresee my state of mind as the date of the conference approached, I would not have attended at all.

Depression is a disorder of mood, so mysteriously painful and elusive in the way it becomes known to the self as to verge close to being beyond description. It remains incomprehensible to those who have not experienced it in its extreme mode, although the gloom, “the blues” which people go through occasionally and associate with the general hassle of everyday life are of such prevalence that they do not give many individuals a hint of the illness in its catastrophic form. But at the time of which I write, I had descended far past those familiar, manageable doldrums. In Ohio, I am able to see now, I was at a critical stage in the development of the disease, situated at an ominous way station between its unfocused stirrings earlier that winter and the near-violent denouement of April, which sent me into the hospital.

I returned to Virginia Tech and sought immediate psychiatric help. I told them about my symptoms, and how I struggled with my classes. They were amazed that I had taken so long to seek treatment. I had attempted treatment in the past, but was always turned away because they were unable to see me regularly enough to give me proper treatment. This time, they were not going to tell me the same. It was arranged that I would see a psychologist one week, and a psychiatrist the following, so that I would meet someone weekly. However, that is not truly enough for someone who is suicidal. They wished for me then to also come in between 8-9 am, when they are open for walk-ins, but because of my inability to fall asleep, I often slept during this time.

The solution that the counselors came up with was to bombard my system with anti-anything drugs. I was taking three antidepressants. Of those, one was for depression, one was to balance out the first, and the third was to balance the first two, while also combating the erectile dysfunction that occurred because of the antidepressants. Being 22 years old, having erectile dysfunction only made me more depressed. On top of those, I took Lorazapam for when I had a bad panic attack. However, I also had Clonazapam that I took every morning to calm my heart when it was bombarded with all the antidepressants that I was taking. And, since all those pills made sleeping difficult, I was prescribed Trazadone to act as a nightly tranquilizer. Of these pills, which now totals six, nothing helped except the Adderall that my friend gave me from his own pill collection, because i was so drugged up that I was unable to focus on academics at all. I spent three months getting my ass kicked, not by school, or dreams, or a lack of sleep, but because the incompetence of Cooks Counseling Center at Virginia Tech to properly attend to its students. I developed drug addictions to Lorazapam and Trazadone, and was given the nickname Mr. Benzedrine by the freshman cadets, giving homage to the Fall Out Boy song.

Needless to say, I withdrew from the university that semester. I stayed on campus, graduating from the Corps of Cadets, but it has little meaning to me now. What I wanted most at this point in time was to leave the university, but to do so with a degree. However, since I was unable to properly function enough to attend classes, I was unable to do so.

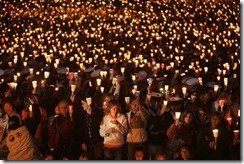

The vigil was not the same either. No longer was the vigil about mourning those that had passed. Much of the university had moved on, or wanted to deal with the remembrance in their own way. The new students saw the event as a photo opportunity. To them it was something that was incredible to see and witness, but not to be a part of, and therefore alienated me even more.

This was the hardest year yet, and for good reason. Being stuck at a university, with little alternatives to leave, and a yearning to just move on with life, while taking something from the university, as in a degree that I felt deserved of, was not within my grasp, and so I would have to return yet once more to the place that would haunt my dreams.

…

I will continue to add more posts, leading up to the 16th, documenting my journey over the past 3 years.

Part 5: 3 Years Later

Part 4: The Midnight Disease

Part 3: Insomnia, the New York Yankees, and the First Memorial

Part 2: The Media, Family, Friends, the West Point Summer, and the Decision to Return

Part 1: The Beginning of the Week

We will Prevail. We are Virginia Tech.

April 16th, 2007